How to begin? Tips to capture an audience in the first sentence

Jun 03, 2025

Why my brain wants to skim your paper

Over and over, I read and review journal papers that start with the same sentence. It is always some version of: Urban populations will exceed 70% by 2050 (United Nations citation). This statistic is then related to the immense food production needed to feed growing urban populations, which is then related back to dependency on the declining rural populations (who grow the food). Climate change is then mentioned as an exacerbating factor. In fact, as I was writing this blog, I also started reviewing a paper that starts with: Currently, 4.4 billion people (or 56% of the world's population) reside in urban areas, and by 2050, that number is expected to have more than doubled (The World Bank, 2023). When did this become the standard opening line—in my field?

These are critically important and alarming evidence-based projections. Yet, when repeated ad nauseum at the beginning of countless journal papers, I find myself falling asleep before I even get to the point of the paper. I am being harsh for sure, but human brains are wired to seek patterns. If the pattern my brain detects is something I’ve seen repeatedly, it reverts to skimming mode. I continue skimming the paper with an expectation that the contents will simply confirm what I already know—the authors will confirm but not extend my knowledge. In short, I am not reading from a place of curiosity.

While the majority of scientific inquiry is meant to empirically confirm hypotheses and assumptions repeatedly over time and different contexts, scientific papers are meant to move us forward (even just an inch—or a centimeter) in our knowledge-base. But papers have another function too: to get us excited about what others are doing and be inspired to take the next step—perhaps in a direction we hadn’t considered before reading the paper.

First impressions matter

Excitement begins with the first sentence. It sets the expectation of the reader. And it is within your power as the author to control. Which isn’t to say you can control the mind of your reader, but rather I want to encourage you to think carefully about the first impression and what kind of mindset with which you want your reader to approach your paper.

So let’s talk about how to begin—how to capture your audience with the first sentence.

A few tips:

- Don’t underestimate the power of a hook

- Assume the reader will skim after the first sentence(s)

- Write something compelling

- Spend time thinking about it

- Revise it until your manuscript is complete

I am going to need another cup of coffee

Here is where I admit I am guilty of rote beginnings. In fact, when I started writing journal papers, I tried excruciatingly hard to replicate the most well-known, most generic summaries of the broad issues in my field. Snore.

Coming from a creative writing background, I thought the point of scientific writing was to be as boring as possible—no adjectives or adverbs unless they were measured data attributes. And definitely nothing narrative that could be mistaken as editorial. Double snore.

Yes, scientific writing should be simple and precise, and interpretation should be grounded in evidence with a tingle of skepticism. What I struggle with is: where is the voice of the author? Where is the passion or conviction?

Why can’t a scientific paper be compelling?

Why does our scientific passion dry up on the paper?

We don’t conduct research because we have to. We don’t fall into very specific niches of inquiry because there is nothing else to do with our lives. We don’t spend endless hours analyzing, contemplating, debating what it all means because we are bored. We do it because we are motivated, inspired, driven, fired up. So why does that all dry up on the paper?

Don’t get me wrong, I am not suggesting opinionated over-reach—which I see all-to-often. What I argue for is to meet you, the author(s), before I read the details of your work. Who are you? What is your angle? Where are you starting from that is unique?

I want you to wake me up!

Sidebar: The first sentence is the tip of the iceburg (so to speak) of the first paragraph, which has to do some heavy lifting. A provocative first sentence doesn’t excuse you from crafting a strong first paragraph…which requires:

- A succinct summary of the broad context

- Summary of the who, what, when, where, and why of your topic

- Establishing the importance of your topic

- Importantly, your reader should know (explicitly or intuitively) the general topic of your paper after reading the first paragraph.

Write a provocative first sentence

I started searching through recently published papers in MDPI with the intent of making of list of examples. But after arbitrarily selecting the first article listed under about a dozen journals and finding nothing to put under the “inspiring” list, I moved to Elsevier. And went down another rabbit hole of generic startups. Here is a short list of some first sentences I thought could be improved (note: citations are excluded in the interest of not singling out specific papers, but rather calling attention to the generic phrasing):

- Globalization has raised questions regarding the need for each country to be self-sufficient and feed its population by producing new protein sources with controlled costs.

- Air pollution is affecting the world’s climate and ecosystems and has significant negative effects on human health.

- In recent decades, urbanization has reached unprecedented levels. More than 70% of the world’s population now lives in urban areas.

- The rapid advancement of information technology and the prevalence of the use of communication devices have significantly reorganized the temporal dynamics of the modern workplace.

- Sub-Saharan African cities are undergoing rapid demographic growth and spatial expansion. More and more people live far away from job opportunities and urban amenities.

- Urbanization is rapidly reshaping global demographics. At present, more than half of the global population resides in urban settings, and this number is expected to reach nearly 70 % by 2050.

- The rapid developments in connected technologies, Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI) and driving autonomy may transform cities and their transportation systems.

- As urbanization advances, the overlap between nature, cities, and human beings increases, creating an ecosystem in urban spaces in which wildlife enter, dwell, and evolve.

- The unprecedented worldwide urbanization since the mid-20th century has resulted in profound changes in the socioeconomic and built environments in the cities of major industrial countries.

- The relationship between science and design is complicated and controversial.

- Land is a multifaceted product of interactions between natural processes and human activities.

- Dryland fields are cultivation areas characterized by arid soil conditions. Throughout the long history of agricultural production, humans have developed the practice of growing drought-tolerant crops—such as sorghum, wheat, corn, and soybeans—on such lands.

Are you asleep yet?

Here are a few that are a little better because there is more specificity…but they do not yet hook the reader:

- The urban night has become one of the new arenas where creativity and social control, privatisation and liberalisation unfold and clash.

- In the contemporary neo-liberal city, where populist anxieties position strategies for urban planning such as 15-min neighbourhoods as an infringement of civil rights and where pseudo-public or ‘POP’ spaces, outsourcing of public services and demunicipalisation are on the rise, questions of who decides what infrastructure is available, how it is resourced and regulated, and who can access it are foundational to cultural democracy and place governance.

- Punjab’s dairy sector contributes 70% of Pakistan’s milk production and supports 8 million rural households; it faces unprecedented challenges from climate change.

Can you write a first sentence that is topic specific and sparks a debate, incites reaction, causes a fleeting stir?

Maybe your response is that a compelling first sentence goes against the accepted format of a journal paper. I disagree. I think we are overlooking an important opportunity to set up our big idea—the core argument of our paper—from the very first sentence. Give a glimpse! Suggest a counterpoint! Lean into devil’s advocate! Ask a red herring question! Rather than putting your reader in the ‘Yeah, whatever, I already know that’ mindset, what would give them pause and say, ‘Wait a minute—I have a strong/different/inconclusive opinion on that!...Let me read further…’

Let’s go back to basics

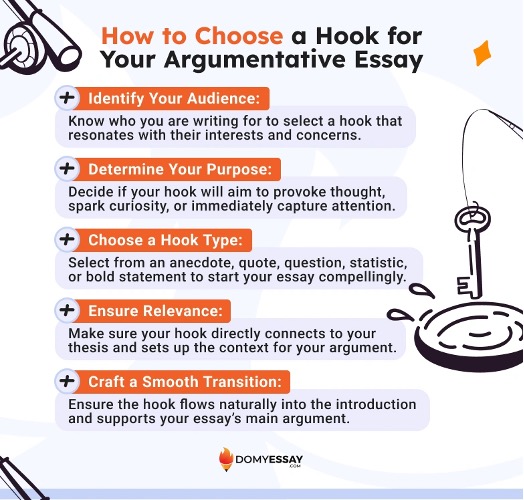

I found a fun blog on how to write a hook for an argumentative essay.

The author lays out six types of hooks:

- Question Hook: Asking a question is a great (and simple!) way to get your readers thinking.

- Quotation Hook: A quote from a well-known source that perfectly matches your point can give your essay a strong start.

- Statistic Hook: Leading with a surprising or impressive statistic can grab attention fast.

- Anecdotal Hook: Telling a short story can make your essay feel more relatable.

- Declaration Hook: A bold statement hook is direct and confident, letting your readers know exactly where you stand from the start.

- Descriptive Hook: A descriptive hook uses vivid language to create a scene, helping your readers visualize your argument.

Takeaways: Who is your audience and how do you want them to react? Experiment with several types of hooks. Make sure your hook relates to your broader context and that it flows directly to the main thesis or core argument of your paper.

Hook your reader with the journey of a ‘Scientific Arc’

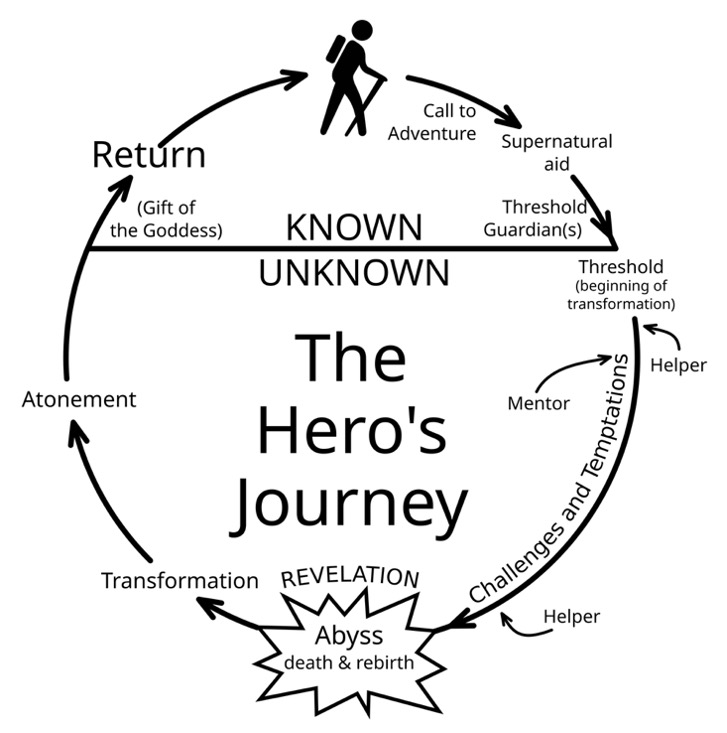

Then establish your authority. Go back to the broad summary. Articulate the status quo. Critically review the literature. Provoke, establish, and, finally, offer your big idea. Just as in fiction with a hero’s journey, we too can create a narrative scientific arc. We too can tell a compelling story—embedded in evidence-based discourse, of course.

By scan from an Unknown authorpublication by an / anonymous poster, in a thread, gave permission to use it. Re- Vectorization: Slashme - 4chan.org, thread about monomyths, AKA the hero's journey, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10284342

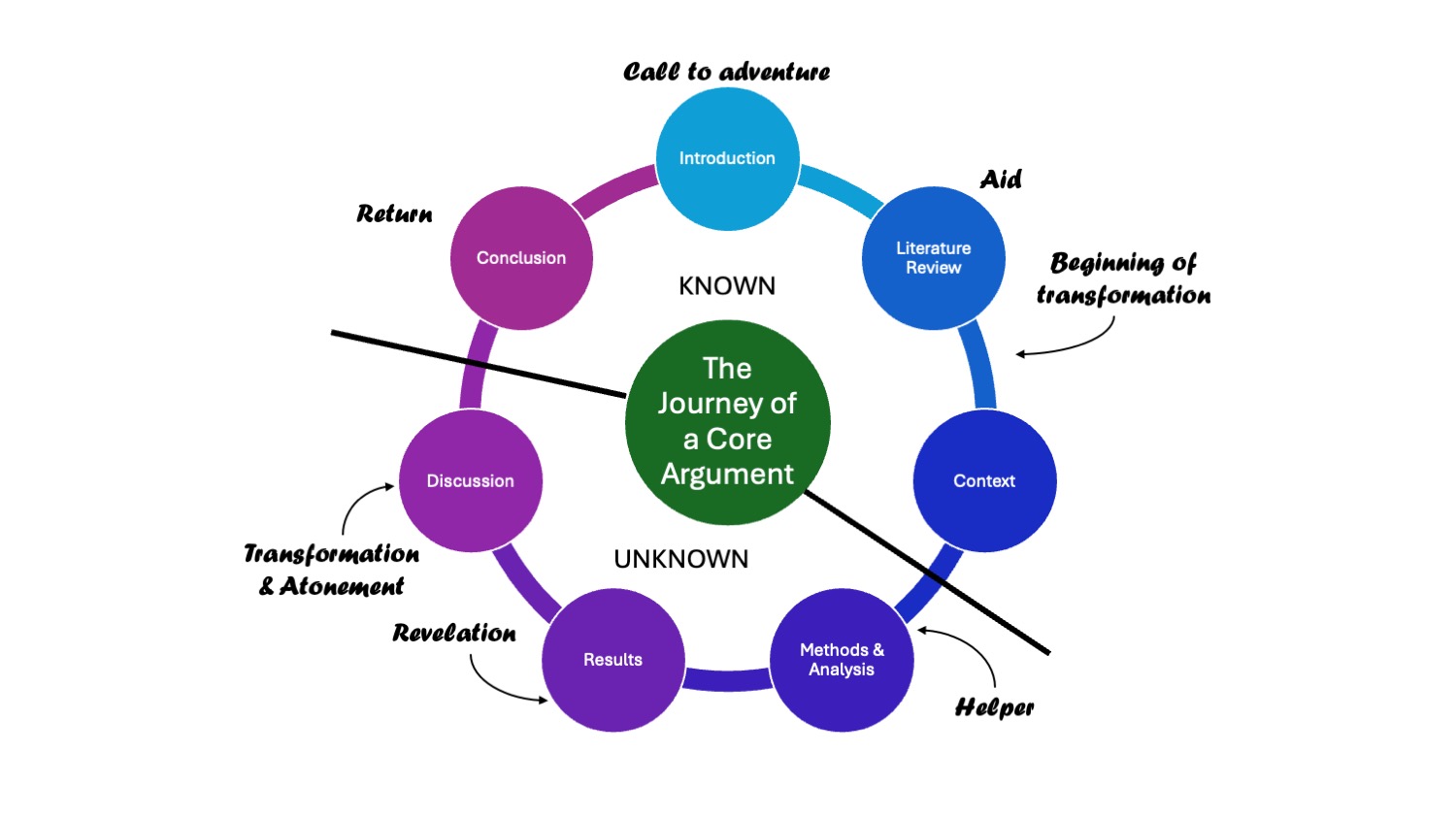

Not a perfect diagram, but I had some fun trying to translate the hero’s journey into a ‘Journey of a Core Argument.’

Let me know what you are working on—send me your first sentence and let me know if you want feedback. As a social scientist and a creative writer, I love the challenge of crafting a scientific voice.

Finally, check out my free video this month on how to turn your dissertation into a journal paper.

And while you are at it—join the Publish It! Community and share your experiences with other academic writers. It’s free!