Three approaches to conducting a literature review… analog, digital, and AI-assisted

Oct 01, 2025

Don’t start from scratch!

The literature review usually takes me the longest time as compared to the other parts of drafting a journal paper. This should be the easiest because it’s based on others’ work; however, it is probably the hardest to get right. Millions—yes, millions—of new papers are published every year, and the number is growing exponentially...it can feel overwhelming to cover it all in your review of the literature. Luckily you don’t have to! You should have already completed a review of the literature for your research grant or project proposal—start there and fill in the gaps! You should not have to start from scratch!

What is a literature review?

A literature review is not a summary of the literature, but let me just make sure everyone is up to speed on what exactly the purpose of it is in a journal paper. A literature summary is a list of key points from a paper, whereas a literature review is…

|

I bring this up because I review journal papers regularly that summarize rather than review the literature. Understandable because the introduction is meant to provide an overview of current knowledge. But it’s time to go beyond a summary of the literature. The aim is not to cut-and-paste and link together a series of sources but rather to elevate your own ideas as a logical conclusion based on your critical integration of the existing literature.

As you begin to organize and structure your literature review, consider:

- First, you may or may not have to or want to summarize and cite the theoretical literature; however, everything is based on some theory so it’s prudent for you to at the very least be aware of your foundation—even if you don’t cite it.

- Second, (and I already mentioned this, but I need to mention it again!) you probably have already reviewed the secondary literature extensively as part of your research grant or study proposal—don’t start from scratch!

Check out this short video to help kickoff your literature review. I talk about how to start, organize, and conclude with your research gap and argument as anchors. The aim is to engage the discourse as it relates to your core argument. Find the full version included in Draft It! The Essential 10-Week Workshop – a self-paced course. Find it on the Publish It! website.

Read, read, read—but not too much!

You’ve read a lot! You wouldn’t be preparing to write a journal paper if you hadn’t already immersed yourself in the scientific discourse. Trust yourself. You’ve already created new knowledge—it’s time to share it. At a high level, here is what you need to consider and have handy as you begin to write:

- Theoretical literature – Know your foundation

- Secondary literature – Know the discourse

- 5-10 most relevant, recent (no older than 5 years) papers on your topic

- Note foundational works as you read and scan references; add max. 5 more papers to review

- Focus on papers in your discipline or closely related using the same approach (context, methods, theoretical lens, etc.); read newest to oldest

- Hint: Begin with the paper most closely matching your topic and expand your search by looking through the paper’s most relevant citations (matching your topic)

- Primary literature – Read with care and take copious notes

A comprehensive tutorial on how to write your introduction including the literature review is part of the Essential Draft It! …I give hints on how to be efficient (including how to step back!), notes for taking notes, advice on how to deal with inherent citation bias, plagiarism—what it is and how to avoid it, picking citation software, selecting a style guide, and more!

My guide to getting started…

Complete these tasks and your introduction including literature review will have all the essentials required for a publishable paper:

Paragraph #1: What is the big picture context that needs to be described to set up the background for your topic? Option to introduce your core argument.

Paragraph #2+: What do we know about your topic? Critically summarize the literature (theories, methods, findings that you intend to challenge, modify or expand upon).

Paragraph #3+: What don’t we know about your topic? What are limitations, persistent questions, gaps in the research (that you will address)?

Paragraph #4: (Re-)introduce core argument. Answer, ‘So what?’ How are you filling the gap, why does it matter, what is novel about your study?

Ok, time for the nitty-gritty: how to approach a literature review. There are numerous resources online for conducting a literature review (which online databases to use, developing search parameters, summarizing texts, identifying themes/patterns, etc.)…I encourage you to check with your institution’s online resources, do a simple online search, or ask AI.

What’s more interesting to me today as I write this blog are the different ways you can approach a literature review—the instruments at your avail. I have experience with analog and digital approaches, and we are well aware that AI is gaining traction (with caveats). I urge you to try different approaches and figure out what works best for you and under which conditions.

An analog approach

I know this will age me, but don’t underestimate the impact of pen and paper. When I was working on my dissertation proposal (not quite a million years ago but definitely in the double digits), I decided to try an analog approach to summarizing the literature on my topic. I needed to dig deep and broad, and I knew that hand to paper would help me record more information in my brain.

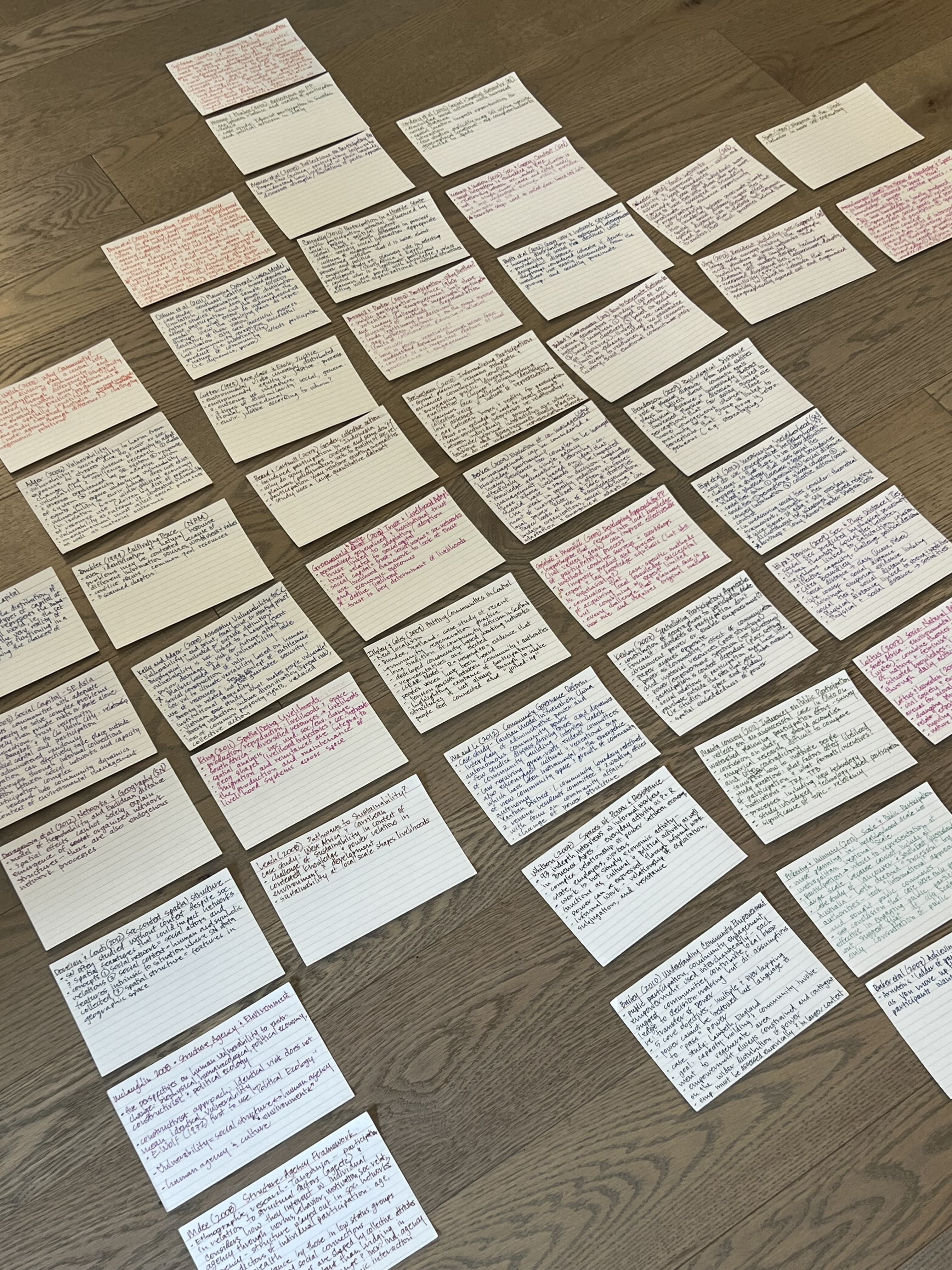

Basically, I created a notecard for each journal paper I thought could be important to cite as part of my synthesis. My method was to create a bullet list of the most relevant parts of each paper—be it a theory, definition, method, case study, etc.—for my specific need. At the top of each notecard, I wrote the abbreviated source as: First Author (Year) and then a word or phrase to remind me the reason to cite that paper. For examples, spatializing livelihoods, informalizing participation, and measuring ‘neighbhorhood’ re: social networks. I also added a note on which discipline(s) the author(s) were situated in, in my case: planning, geography, sociology, etc.

Limiting each paper to a single-one-sided notecard summary forced me to be concise. Notecards in hand, I could easily sort, organize, and identify patterns—and gaps—manually. I could also easily see where I was missing information.

Analog methods take a little more time to produce but are more flexible when it comes time to ‘analyze, synthesize, and critically evaluate.’ Handwritten notes also make it more difficult to accidentally plagiarize because it removes the ability to copy-paste. Furthermore, notecards can be re-sorted, edited down, and added to for future papers.

Digital standard

Conducting a literature review using digital methods is for sure the most common approach (for now?). After years of organized digital chaos, I found a method that dramatically reduced the amount of time I needed to prepare to write my literature review. It’s a method described in detail in Belcher (2019)[i], but I’ll give you an example of how I conducted a literature review in three days. Yup, three days. It was at a moment when I realized I had grant money expiring in less than a month and I had funds earmarked for Open Access (OA) publication.

I refused to let the funds expire so I targeted MDPI’s Sustainability Journal. Knowing they had a 10 day review policy, left me a maximum of two weeks to draft and submit my paper. Here is how I did it:

First, I generated a list of context topics including my original / primary literature for the paper (most of which I’d already summarized elsewhere so I ‘just’ needed to repackage it). Here is my list of topics:

- Urban food system concepts - theory/general

- Characteristics of urban agriculture (form and function and actors) - typologies/examples

- Sydney food system and urban agriculture – context

- Linking individual components (i.e. farm) as a system (i.e. farm to table) - gap & research overview

Next, I brainstormed (and articulated) how I could limit my reading of the contextual literature for the paper. Here is my list of parameters:

- Find a good book on urban agriculture (options: Integrated Urban Agriculture??? Sustainable Urban Agriculture???)

- Supplement with journal articles

- Limit to most recent publications

- Limit to 10 new sources max

I identified the methodological literature that I needed to cite from my existing library (not all papers require this, but it made my introduction stronger) (again, this was already summarized in my other outputs but required revision to align with the core argument of the paper and to avoid self-plagiarizing):

- Social networks

I identified the theoretical literature that I needed to cite from my existing library (not all papers require this, but, again, it made my introduction stronger) (again, I’d already written this up previously, but needed to revise it):

- Food systems

Then I asked: What’s the entry point? How do I show how my argument relates to previous arguments?

- Answer: More than form and function, actors and social networks help us understand how urban agriculture manifests and the sustainability of the system

It was time for me to dig into the secondary literature. I selected 10 papers from my existing catalog (that I had cited in previous papers, on the grant proposal, etc.) and added 5 more from a quick topic search on GoogleScholar—focusing on the most relevant, recent, and useful in terms of covering or updating my theory, methods, case studies, definitions, etc. Here is where the hard work started: from this list, I skimmed each paper and copy-pasted a bullet list of important text into an Evernote document.

I like Evernote, but citation software (Endnote, Mendeley, etc.) can also be used to take notes and output basic summaries.

Next, I read through the copied text across the 15 papers and highlighted what was most relevant. Then, I put my Evernote document away and tapped my brain to synthesize: what did we know about my paper topic? What didn’t we know? And what was the gap I would fill. Finally, I went back to my literature summary and pulled out more specific language and details (e.g., case studies) and inserted the relevant citations.

Another thought: If you are into qualitative coding, Atlas.ti can be used to conduct literature reviews. I’ve wanted to try it out, but alas, my subscription has expired.

AI-assisted

As we become more comfortable using AI—and consequently integrate it more into our lives—it is inevitable that literature reviews will increasingly make use of it. I recently blogged about this in:

AI-assisted literature reviews: How and when to effectively use artificial intelligence

From the blog, here is a summary of when and how to use AI:

- Conducting: Use AI for an initial search and overview of the literature, especially when exploring a new or broad topic. AI can help provide a comprehensive list of studies and highlight key research questions.

- Assisting: Use AI to synthesize and structure your review. It can help organize the review into logical sections, summarize studies, and suggest transitions.

- Filling Gaps: AI can assist in finding missing studies or research you’ve overlooked, especially if you feel there are underexplored areas in your review.

- Editing: AI is ideal for polishing your writing, improving grammar, clarity, and ensuring the paper follows the right citation format.

Here is some advice (from Claudi.ai) on how to construct your prompt to ensure validation of any search outputs from AI and reduce risk of hallucinations:

Prompts should include explicit requirements for verifiable citation details. Requesting DOI numbers, specific page ranges, journal volume and issue numbers, and complete author institutional affiliations creates checkpoints that can reveal fabricated citations (Anderson & Park, 2024). Additionally, instructing AI systems to provide brief abstracts or key findings from cited sources can help identify inconsistencies or fabricated content.

Note that ethics require transparency in use of AI to write a scientific paper…every journal publisher has already developed policies, see for examples: Elsevier and MDPI. Check the publisher of your target journal in advance.

Get creative!

There is no one way to conduct a literature review—figure out what works best for you. Different approaches might be quicker, but you might also sacrifice depth of critical analysis. On the other hand, no review of the literature can cover everything: know when to stop. You are not an encyclopedia; rather think of your introduction and literature review as a conversation with a (silent) audience. One that surely will talk back through reviewer comments—anticipate and be proactive as you curate your contribution to the discourse.

If you only plan to write one paper, then you can go for the quick and messy approach. If, however, you are on the long journey of building your body of research, I urge you to test out different approaches and lean into what feels most sustainable—and doesn’t require you to start from scratch ever again.

Footnotes

Finally, check out my free video this month on publishing null hypotheses and contradictory findings. You can find it here.

I’ve also moved all my free short videos to my YouTube channel, check them out here.

I upload new content monthly so subscribe if you are interested!

And while you are at it—join the Publish It! Community and share your experiences with other academic writers. It’s free!

Note: I don't receive any incentives for clicking links in this blog.

[i] Belcher, Wendy Laura. Writing your journal article in twelve weeks: A guide to academic publishing success. University of Chicago Press, 2019.